Housing for people with disabilities: what needs to happen

This week, the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability turned its attention to group homes.

While I am a person with a severe physical disability who has never lived in a group home, my research and advocacy has always focused on how Australia can move beyond congregate (group) housing for people with disabilities and towards a future where people with disability can choose where we live, who we live with, and how we are supported.

This is absolutely critical if we are ever to do something about the high levels of abuse and neglect that people with disabilities experience.

It is also critical if we are to meet our international human rights obligations.

Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disability (UNCRPD) states:

“Persons with disabilities have the opportunity to choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement.”

Despite the fact that Australia signed up to the UNCRPD in 2008, we are still a long way from achieving this goal.

Almost 6,000 young people with disability still live in residential aged care.

More than 17,000 people with disability currently live in group homes – sharing their home with unrelated adults who also happen to have a disability. Most are forced to live in these circumstances because they have no other options.

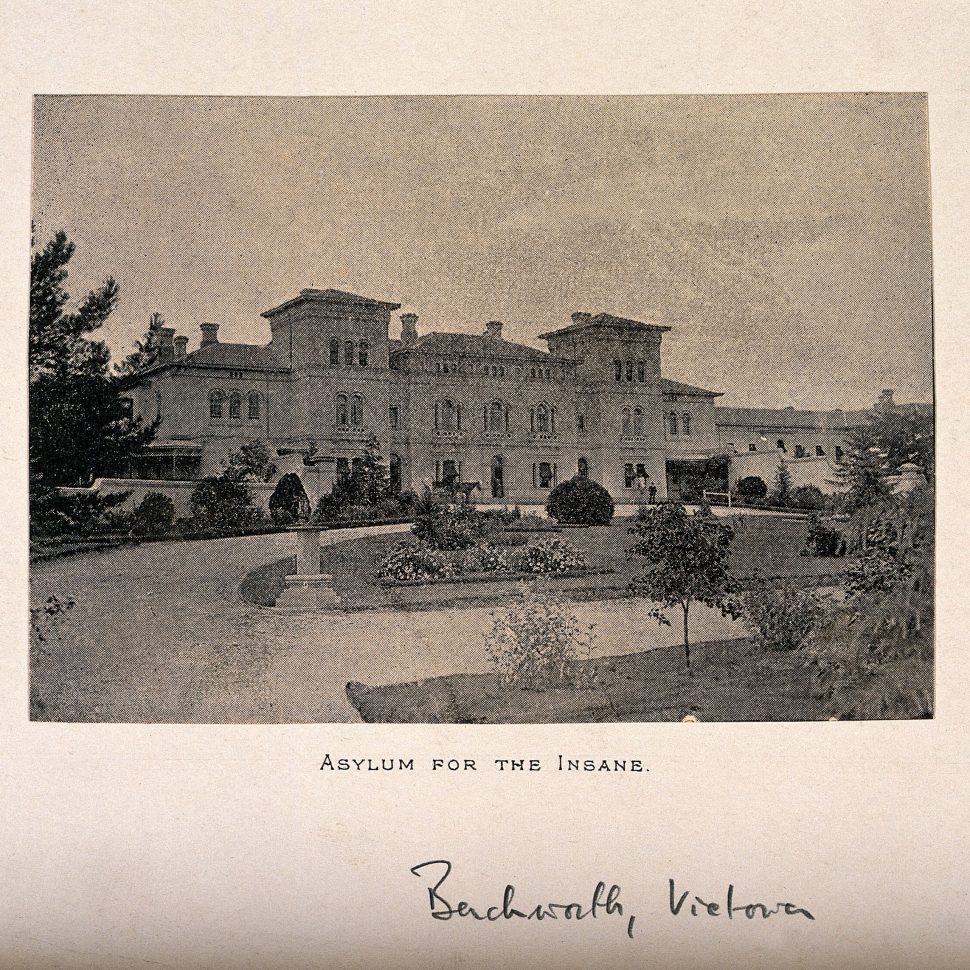

Once upon a time, group homes were seen as innovative – and they were when compared to the large institutions that they were built to replace. But however they look from the outside, most group homes in Australia today are just mini-institutions. They are not much more than scaled-down versions of what came before.

We heard many terrible stories this week from people with disability and their families about the abuse and neglect they experienced in group homes.

But we also heard stories about grown adults being forced to go to bed at 7pm. About staff wandering in and out of bedrooms without acknowledgement. About being forced to go to out to an activity when all you really wanted was to stay home for the day.

The thing all these stories had in common was a lack of control. A lack of choice. An inability to do things the way you wanted them done.

For too long, people with disability have been forced to accept the latest vacancy in a home with people they have not chosen to live with. So if the living situation turns out to be unsuitable (at best) or abusive (at worst), they have nowhere to escape.

And despite the introduction of the NDIS – group homes continue to be the dominant housing option for thousands of people with disability in Australia.

Dr. George Taleporos fr Summer Foundation at #DisabilityRoyalCommission –

Comm Atkinson: I see that #grouphomes are now being called…shared supported accommodation.

‘There are lots of lovely words for group homes. Accomod’n community residential unit, a sh*t place to live.’ pic.twitter.com/Wa0dRxkPvd

— Norman Hermant (@NormanHermant) December 5, 2019

The NDIS and housing

Participant choice and control is a key principle of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) payments made by the NDIS make it possible for people with disabilities to have more choice about where we live. Instead of the government providing funding directly to the housing provider (who also managed the services inside the house), the funding for SDA now goes to the participant to spend where they choose.

But only a small number of NDIS participants are eligible for SDA.

And that’s not the only problem when it comes to the NDIS, choice and control, and housing.

Some NDIS participants are still being funded for shared living when they have expressly stated that they want to live on their own or with family or friends – not in a group home environment.

And there are serious conflicts of interest at play, with some housing providers also acting as support coordinators. Support coordinators are people funded to help the participant navigate their options – like choosing where they live and who should provide their support.

We are also seeing housing providers lock people into specific support providers for their projects. This practice not only robs the person with a disability of choice and control over their service providers, it also breaches Australian Consumer Law.

There are also support providers who are providing housing at “no charge” to their customers. This may seem generous at first – but it’s not. Service providers are housing people in large group settings, using the income from the support payment to pay for substandard housing, and avoiding the necessary regulation that must be met by housing providers. The person with a disability does not benefit – instead they have important safeguards removed by the provider that they are now captive to.

What needs to happen?

We need the fulfilment of our rights to live like everyone else.

The government must commit to building more affordable and accessible housing.

It should be mandatory to build all new homes in Australia to a minimum of Livable Housing Australia gold standard.

Through the NDIS, people with disability must be supported to develop and implement our own vision for independent living that can maximise our chances of getting an education, getting a job, developing relationships, and getting a life.

This must include support to explore our housing options and to decide for ourselves where we want to live and how we want to be supported.

This means we need access to both independent support coordination and independent advocacy. Advocacy is grossly underfunded in this country and that needs to change if we want to solve this problem.

The principle of choice and control must be protected. We must all have access to the fundamental right to decide who we live with, who provides our support, and how we are supported.

We must also take action to free people with disabilities from providers who hold us captive. This is partly about regulation and oversight, but it’s also about building our capacity to make choices, to advocate for ourselves, to understand our rights, to speak up, and to take action against providers that fail to respect our rights.

These things are critical to addressing the violence, abuse and neglect perpetrated against us.

You can watch the Royal Commission hearings live from the Disability Royal Commission homepage.

Join the conversation